By JIM WATKINS, For The Democrat

Of all the Brown County Boys that served in World War II, it could be said none spent more time on the front lines than Robert K. Fox. The “front line” in Robert’s case was not one that probably would have first come to mind such as Italy, or France, or perhaps any number of the better-known island battle fields of the Pacific. No, Robert’s front line was Los Angeles, Calif.

Robert and his brother Edward joined up for a one-year Army enlistment in January of 1941. Pearl Harbor, of course, changed that term of enlistment. Robert was 19 at the time.

Robert was born in Iowa. The family moved to Hamblen Township, Brown County, just across the county line from Bartholomew County in 1930. The Brown County Historical Archives listed Robert as a farmer and a sawmill worker at the time of his enlistment.

After basic training, Robert was assigned to the artillery as his specialized field. His orders then sent him to Fort MacArthur, San Pedro, Calif. Fort MacArthur was named for Civil War hero Lt. Gen. Arthur MacArthur, the father of Gen. Douglas MacArthur.

San Pedro is both part of Los Angeles and part of the Port of Los Angeles. With the events of December 1941, the importance of this port would make Fort MacArthur and its artillery batteries vital to its defense. It was in fact called the “Guardian of Los Angeles,” as the coast’s first line of defense. The fort would have 30,000 soldiers, 5,000 feet of tunnels, and a multitude of gun crews, machine-gunners, and aircraft spotters.

The weeks after the Japanese sneak attack on Pearl Harbor created a wave of anxiety up and down the west coast of the United States. In fact, news media did not hesitate to use the word panic when describing the situation.

Panic may not have been too strong of a word. The situation was especially tragic for the Japanese-Americans who were forced by government decree to vacate their homes and businesses and herded off to relocation camps well away from the coast. No such plan was instituted for German-Americans. The loss of lives and shipping caused by the German submarines on the east coast would far outstrip anything that happened on the west coast.

Just days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, nine Japanese submarines that were part of the attack were given new orders to head eastward and create as much havoc as possible along the West Coast of the United States. This would be the only major strategic offensive by the Japanese navy on the mainland of the U.S.

Thirteen days after Pearl Harbor, one of the subs sank the tanker Emidio off Eureka, Calif., killing five of its crew. Three days later an oil tanker was sunk off Cambria and miraculously all 38 crew members survived. On Christmas Eve 1941, a torpedo damaged but did not sink a lumber freighter with a loss of one of its sailors. Six other tankers along the coast were attacked with little effect and no loss of life.

A torpedo was launched at the Golden Gate Bridge. It did not detonate. It was not discovered until after the war in 1946.

February 23, 1942, saw the first attack on the mainland when a submarine surfaced and fired 13 shells from its deck gun at the Ellwood oil field and caused minor damage. There were no casualties.

These incidents were enough to keep the populace on edge and led to the event remembered as “The Battle of Los Angeles” which took place two days after the Ellwood oil field attack.

Cecilia Rasmussen of the Los Angeles Times revisited the event in a 2002 article.

“Just before dawn radar operators supposedly detected and aircraft believed to be Japanese. The dreaded five blast signal sounded triggering a five-hour blackout. Searchlights beamed; anti-aircraft guns blazed launching close to 1,500 shells. Air raid wardens desperately tried to enforce the blackout.

“But life continued. Hospitals reported 14 babies delivered while the guns roared. The new arrivals were dubbed ‘blackout babies.’ Five deaths — three in traffic accidents, and two the result of heart attacks — were attributed to the blackout.

“As it turned out, there had been no enemy aircraft over Los Angeles. The Army called the incident a case of the jitters.”

The strategic importance of Fort MacArthur grew as L.A. exploded with growth during the war years. The population grew as defense plants seemed to pop up overnight. Men and women from all over the country converged on the city to fill the jobs and play their part in creating the “Arsenal of Democracy” that would be a key element in defeating the Axis powers.

After the initial attempts of the Japanese to spread chaos on the West Coast with little success, their attention necessarily shifted closer to home after suffering a string of defeats by the Allied forces.

At Fort MacArthur there was no letting up in their diligence to protect the city as well as the ocean front now crowded with war ships, troop transports, and freighters carrying all the resources necessary to supply the defense plants. For the artillery crews at the fort, it was drill, drill, and more drill as they launched their shells for practice into empty target zones on a regular basis.

May 22, 1944, was a Monday. Probably not the best day of the week for a drill. A shell exploded. The San Pedro News Pilot would report the details.

“The army did not explain the blast, but Long Beach police said the nitro propellant in the shell case detonated during loading drill when the shell was accidentally dropped on the tile concrete floor of the gun emplacement, overlooking the ocean at Lindero Ave. and Ocean Blvd. A baseball-sized shell fragment flew 150 yards through a fence and crashed through the wall of the home of E. H. Rinquest. There the blast hurled pictures from the wall and dishes from the shelves as it did to another nearby home. At least two shoes blown from the blast victims reportedly were recovered from the ocean. Seven ambulances were summoned.”

Among the crew there would be one fatality and eight injured. The one fatality was Robert K. Fox.

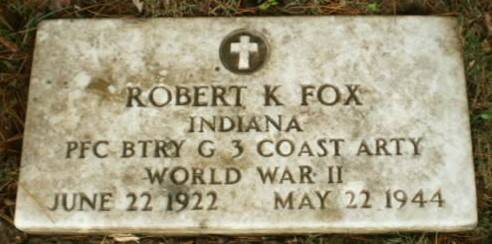

The headstone of Robert K. Fox

The headstone of Robert K. Fox

Democrat file photo

The Democrat of June 1, 1944, reported the funeral services for Robert at the Bond Funeral Home. Robert was survived by his mother Estella Reed, his step-father Dayton Reed, brothers George and LaVerne, and three step-brothers.

Robert is buried at Greenlawn Cemetery in Nashville.

Jim Watkins is a Brown County Historical Society member who wrote “The Fallen,” a memorial document about young men from Brown County who never returned home from World War II. Watkins was a public school teacher for 42 years and has always been interested in learning about WWII. He can be reached at [email protected].

Jim Watkins is a Brown County Historical Society member who wrote “The Fallen,” a memorial document about young men from Brown County who never returned home from World War II. Watkins was a public school teacher for 42 years and has always been interested in learning about WWII. He can be reached at [email protected].

The cover of “The Fallen” by Jim Watkins that memorializes Brown County soldiers who never returned home from World War II. “Every fatality of war is a tragic story. The enormity of it nationwide taxes all comprehension, but when narrowed down to a little rural area of middle America one is more able to appreciate the terrible sacrifices made during that time,” Watkins said.

The cover of “The Fallen” by Jim Watkins that memorializes Brown County soldiers who never returned home from World War II. “Every fatality of war is a tragic story. The enormity of it nationwide taxes all comprehension, but when narrowed down to a little rural area of middle America one is more able to appreciate the terrible sacrifices made during that time,” Watkins said.

Democrat file photo