Hundreds of voters living inside or near Nashville town limits were improperly placed into voting districts an unknown number of years ago.

What effect it might have had on past elections — if any — is unclear.

The problem was discovered about a month ago when Nashville Town Council President Jane Gore visited the Brown County clerk’s office to file for re-election. The county clerk’s office is the voter registration office for the entire county, and it also handles paperwork for all local candidates regardless if they are running for a county, town, township or school board office.

Gore’s candidacy paperwork said she lived in town council District 3, which is the district she represents. But in the statewide voter registration system, or SVRS, Gore was listed in District 2, explained Kathy Smith, the Brown County clerk.

Gore brought in a town map that clearly showed her address in District 3, Smith said. Smith corrected Gore’s record in the computer, then started looking at other voter records.

Smith revealed the problem at the July meeting of the Brown County Election Board.

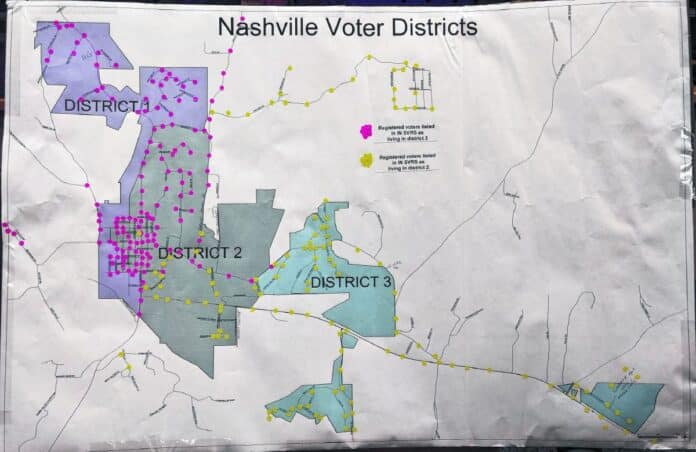

A large map displayed in the meeting room showed the boundaries of the three town council districts and colored dots representing the affected address ranges.

All of the voters who are supposed to be in town council District 1 were listed in District 3 in the computer system, the map showed.

Likewise, all of the voters who were supposed to be in District 3 were listed in District 2.

Seventy-four individual addresses or address ranges (such as “635 to 935 Highland Drive”) were listed in District 2 when they were supposed to be in District 3.

Seven dots — representing individual addresses as well as groups of homes — are outside town boundaries, but they were categorized as in-town voters. Those included all residents of Creamer Drive as well as select addresses on Hilltop Lane, South Drive, West Drive, West Lake Drive, Skyline Drive and Stant Place.

Smith said her “rough count” of how many voters were affected is “around 1,000.” As of July 19, Nashville had 1,023 registered voters.

All town residents vote for all town candidates regardless of what district they live in, explained Brenda Young, Nashville clerk-treasurer. The only time district residency really matters is for the candidates themselves, who have to live in the district they’re representing.

However, having out-of-town voters listed as in-town voters could have been a problem if they were improperly permitted to cast votes for town offices. In a community of 1,000 or so people, a few votes can make a difference.

Young said she talked to one of the out-of-town voters whose property was marked as in town on the map, and that person said he/she did not receive a town ballot in the last election. “If they had received an in-town ballot, they would not have voted, because they know better. … They received a county ballot as they should have,” she said.

“I’m not too sure that just because there’s a dot on here, that they actually passed out the incorrect ballots.”

Brown County Election Board member Brent Biddle asked Smith at the July 11 meeting if any voters had been disenfranchized, or not permitted to vote, as a result of these mixups. Smith said she had no way of knowing that.

However, last week, Smith said some in-town voters may have been miscategorized as out-of-town voters and unknowingly didn’t get the opportunity to cast ballots in the town general election, which often occurs during the county’s election. During those election cycles, a voting location could have multiple types of ballots to give to voters depending on exactly where they live in the precinct.

Arthur Omberg, who was seeking an at-large seat on town council, said he went to vote in-person absentee last fall, before Election Day, and noticed he had been given the wrong ballot because he wasn’t listed as a candidate. He had the ballot that out-of-town voters get in his voting precinct, not the in-town ballot.

“They said there were a few people affected and they would correct it,” Omberg said. “When I went back, I was able to vote for town candidates.”

Omberg ended losing his bid for re-election by 18 votes.

Smith and Young are now working together to verify that all registered voters living in town limits are in the correct town voting districts.

Smith said she has verified that all of the candidates for town offices this fall actually live in the districts they are seeking to represent.

What happened?

Young, who’s been Nashville clerk-treasurer for 32 years, and Smith, who just took office as county clerk in January, don’t know exactly how long these district assignments have been wrong in the computer system or how they got this way.

The last time the town clerk-treasurer’s office double-checked the in-town voters list was in 2003. That was the last time it conducted its own election just for Nashville residents at a time that didn’t coincide with a countywide election.

“This is the first time I’ve seen this map,” Young said on July 19, about the map Smith showed at the election board meeting.

“I was really surprised, absolutely surprised at this.”

The town clerk-treasurer’s office does not have access to the SVRS, Young said. Only the county clerk’s office does locally. While she can give information to the county about the town’s voting districts, Young’s office can’t actually change them in the registry.

Smith had theorized that voters were put in the wrong district in the system when the town annexed the Coffey Hill and Orchard Hill neighborhoods into Nashville, which was in 2011. When the town council passed the annexation ordinance, it was shared with the county clerk’s office, and it included a map of the town council districts, Young said.

Young doesn’t know if that’s how or when this miscategorization happened. Some of the incorrect district assignments are in those neighborhoods, but that doesn’t account for the majority of them.

Judging from the few notes she can find in the SVRS — a system which has changed in recent years — Smith believes the problem occurred around 2010, when the annexation process started.

The SVRS contains a “precinct key” in which the county clerk assigns which areas make up election districts, said Angela Nussmeyer, co-director of the Indiana Election Division.

The few notes still viewable in the SVRS from 2010-2012 show that the county clerk’s office tried to make a change in the system, but Smith can’t tell exactly what they tried to change.

Beth Mulry, who was county clerk at the time of the annexations, said last week that it’s been too long for her to remember how the annexations were handled. “I do know that we were always very careful on voter assignments. We did occasionally find wrong assignments even though,” Mulry said.

Nussmeyer said that it’s “not uncommon for a county to discover voters on a particular street or some other division in an election district or precinct to be misassigned based on how the county user performed their work when evaluating maps and the precinct key, which is why this problem is correctable.”

Figuring out who’s in which district for what races can be tricky because the town’s representation districts do not line up with the voting precinct lines the county draws. Town voters are split between voting precincts Washington 2 and Washington 3, but not all voters at those polling places get town ballots, because Washington 2 and Washington 3 also contain some out-of-town addresses.

Data from the county’s voter registration file is loaded onto the electronic pollbooks, Nussmeyer said. The pollbooks determine which kind of ballot is loaded onto the electronic card which voters are given to insert into their voting machine during general elections, Smith said.

She said it is possible that some voters were given an inappropriate ballot in a past election and might have voted on it — if they weren’t looking for a particular name to be on their ballot like Omberg was.

“A regular voter, if they were going to vote, would probably say, ‘OK, this is my ballot,’” Smith said.

Young received a list from the county clerk’s office so that her office could cross-check the voters listed as in-town with records of town sewer service.

“It’s going to take some work, but we are happy to do it, and actually I would prefer that we get to do that each time,” Young said.

When Young takes that list back to Smith, she’ll start transferring that information into the SVRS. They’ll have to go by the maps and boundary descriptions the town council passed in 2011 to determine who should be in what town council district.

When the changes are finished, affected voters will be sent a new voter registration card, Smith said. This could affect where they go to vote in elections beginning next year. (This November, all town voters will vote at Town Hall.)

“I want to be very comfortable at the time (of the next election in November) that our polling list is correct,” Young said. “We’ll make sure.”