Submitter’s note: This was written by Martha Snyder Weddle.

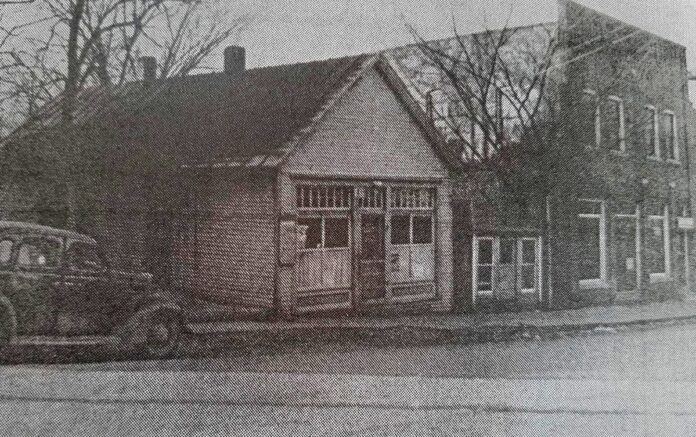

In April 1929 my husband, Monte, our 6-month-old son, Jack, and I moved into the telephone office, a small three-room building on West Main Street between Herbert Miller’s corner drug store and the bank. The corner building is called “Hobnob Corner” now.

The telephone office had one switchboard which was in the front room and one booth with a telephone outside that could be used when the office was closed after 5 p.m. There was a boardwalk on the east side of the building leading to a booth.

I gave 24-hour service, sent and received all telegrams, collected the money for the telephone bills, and received all trouble calls for $30 per month. If there were 31 days in the month the pay was still $30. Besides the $30, we were given our rent, lights and wood.

The trouble calls were taken care of by the telephone men from Morgantown.

All long-distance calls went through Morgantown, then on to Martinsville where the calls were completed. The Martinsville operator was Nashville’s “toll center.” We had just two lines to Morgantown and one line to Martinsville. Morgantown, Nashville and Martinsville used the same line to and from Martinsville for long-distance calls. Sometimes it was one or two hours before a call could be completed. The Martinsville operator had to keep the party on the line until she could get the line to Morgantown and then to Nashville.

The two lines from Morgantown to Nashville were used for local calls also.

Sometimes it was hard to find the Nashville person making the long-distance call by the time Martinsville had completed the call. Often, I would call the restaurant or the drug store looking for the Nashville party while keeping Martinsville on the line waiting.

In the winter, it was an unwritten law that people were not supposed to use their phones after 9 p.m. unless there was an emergency.

In the summer, the farmers started calling at 4 a.m. to arrange different trips: taking a load of hogs or vegetables or melons to market in Indianapolis. In the winter, the calls would start at 5 a.m. if someone was going to butcher and had to let those who were helping know that the fire was going, and the water was getting hot.

Sometimes a person receiving a telegram had no phone. If the person had not lived here very long, I had to make several calls before finding where to deliver the message. Then I had to find someone willing to take the message to the person. The telegraph company would tell me how much they would pay to have a message delivered. Sometimes they would pay 25 cents; other times they would pay as much as $1.

At one time we had a line to Belmont we could use to call Bloomington without going through Morgantown and Martinsville. The line was owned by Bill Exner, a German, who found his way to Brown County. The Belmont line did not always work, for Bill did his own repairing. Often, the line was nailed to trees if the poles were down.

To call Columbus, Indiana, we went through Morgantown, Martinsville, Indianapolis, then to Columbus. If Bill’s line was not working, we had to go through Indianapolis to reach Bloomington. I was always on my toes to complete long-distance calls since the one line couldn’t serve many such calls each day.

We often had 15 telephones on one line. Each party was assigned a special ring — like one long, two shorts; or one long, one short, one long; or two long, three shorts, and so forth.

If I was sitting at the switchboard when a person rang, a little door dropped down and made a zip sound (no bell rang) and I knew a call was coming in. Underneath the door there was a small hole and I plugged in a cord, and then opened a key to talk to the party. I took the mate cord and plugged it into the number the party was calling, then pulled back on the short key with my left hand and turned a crank with my right hand to ring the number. It was a two-handed job.

Every now and then I opened the key to hear if the parties were still talking. If there was silence, I asked, “Waiting?” If the answer was yes, I closed the key. If there was no response, the call was finished, and I unplugged the pair cords. There were 12 pairs of cords; 12 calls could come in and be made at one time.

There were very few private lines. Private lines were in businesses and doctors’ homes. A few people like Leatha Walker, the funeral home, the grocery stores, also Leila David’s Motel had private lines.

As I knew almost all of the customers, often a person would call me and say they were going to their mother’s and I would make a note of any calls they received. Other times someone would ask me to call a friend to tell her she had gone to Columbus or Bloomington.

I was called when someone was having a bridge party and told who could be reached at the various homes if calls were expected.

Nashville had no running water. Either I or my husband carried water from the courthouse pump or the Village Green pump to the house to use for all our needs.

There were three telephone offices in Brown County in 1929: The Nashville office, Bill Exner in Belmont, and an office in New Bellsville that went to Columbus.

Mrs. Clyde McDonald was the Nashville telephone office manager before I was.

Submitted by Pauline Hoover, Brown County Historical Society