Sarah Noggle sits at a large, flat table in her textile gallery, surrounded by woven rugs and spools of threads in every color you could imagine.

The textile artist is handling a fragmented linen piece at the table that resembles an ancient artifact, pieced together as a puzzle.

She scrapes the dry and brittle linen with a pallet knife, unearthing dried adhesive that was used to attach the linen to a piece of burlap more than 60 years ago.

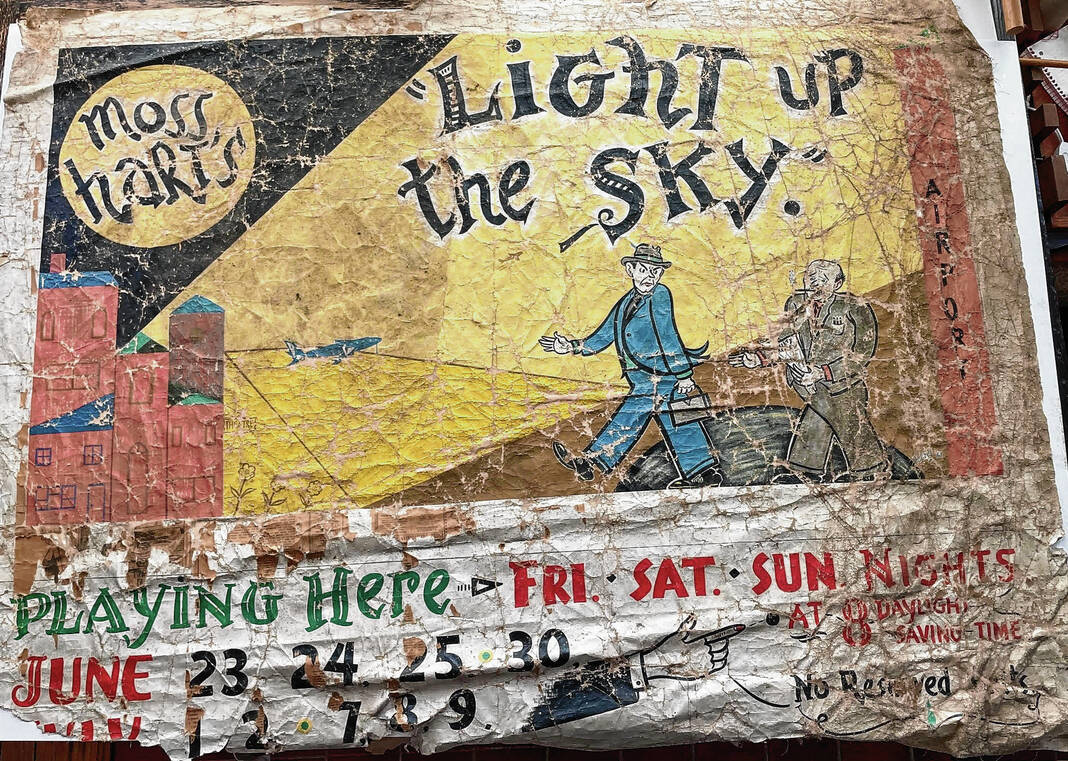

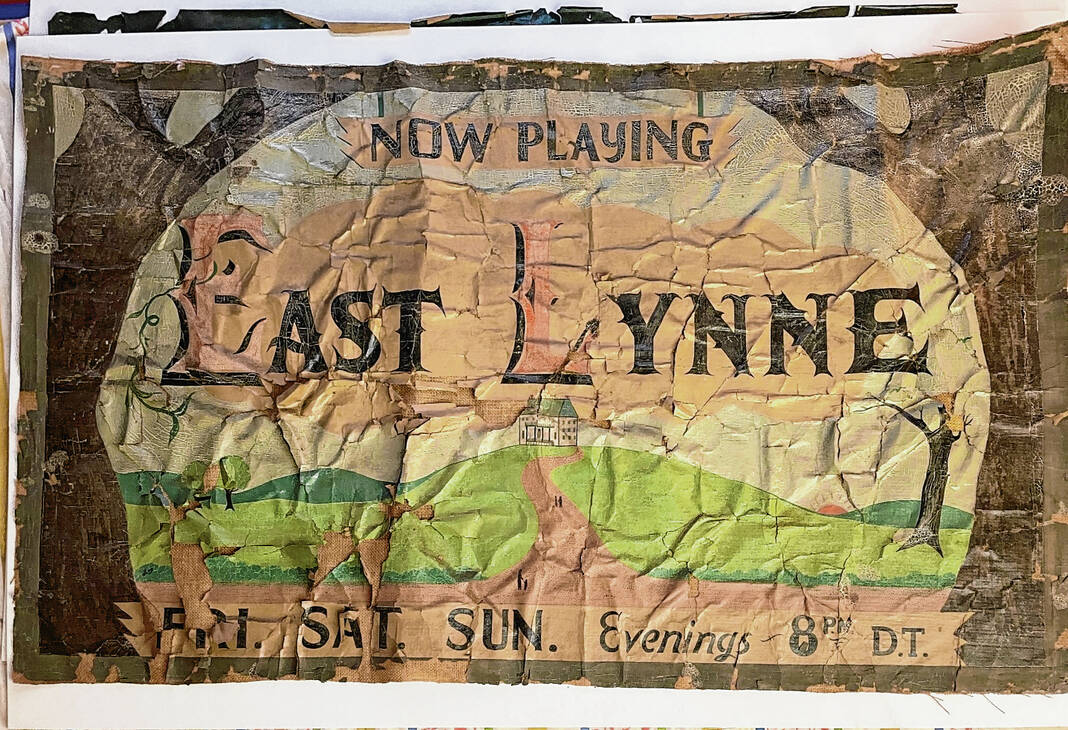

On the other side of the tan, mildew-laden linen is a painting with the words “East Lynne,” the title of a play that once graced the stage of the Brown County Playhouse.

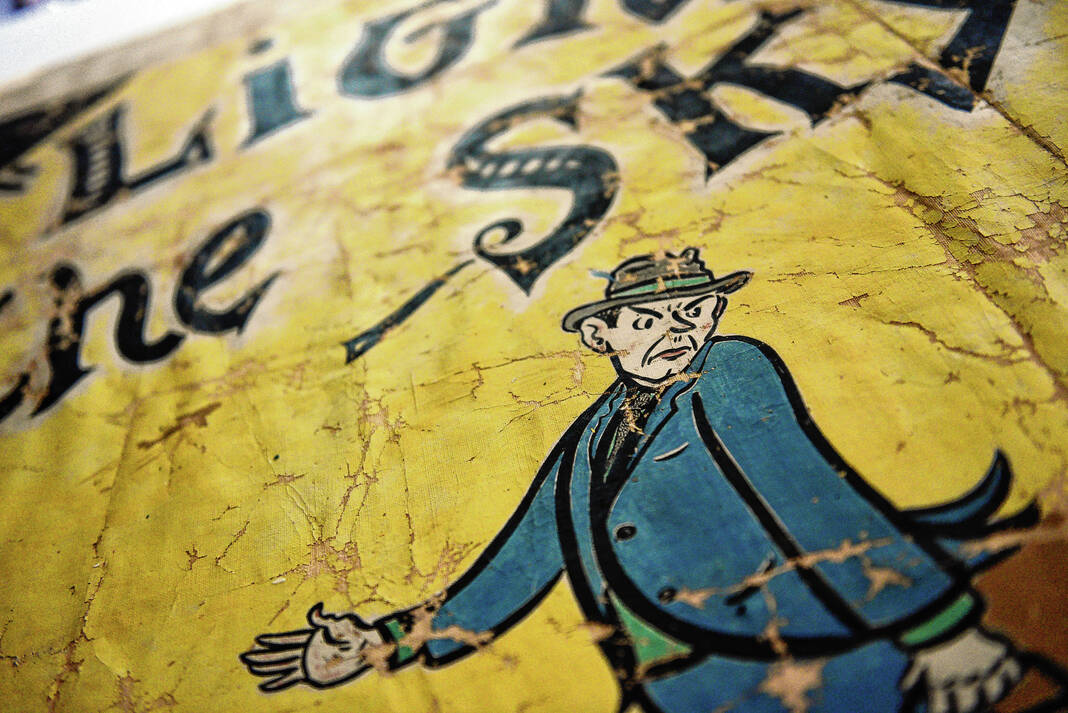

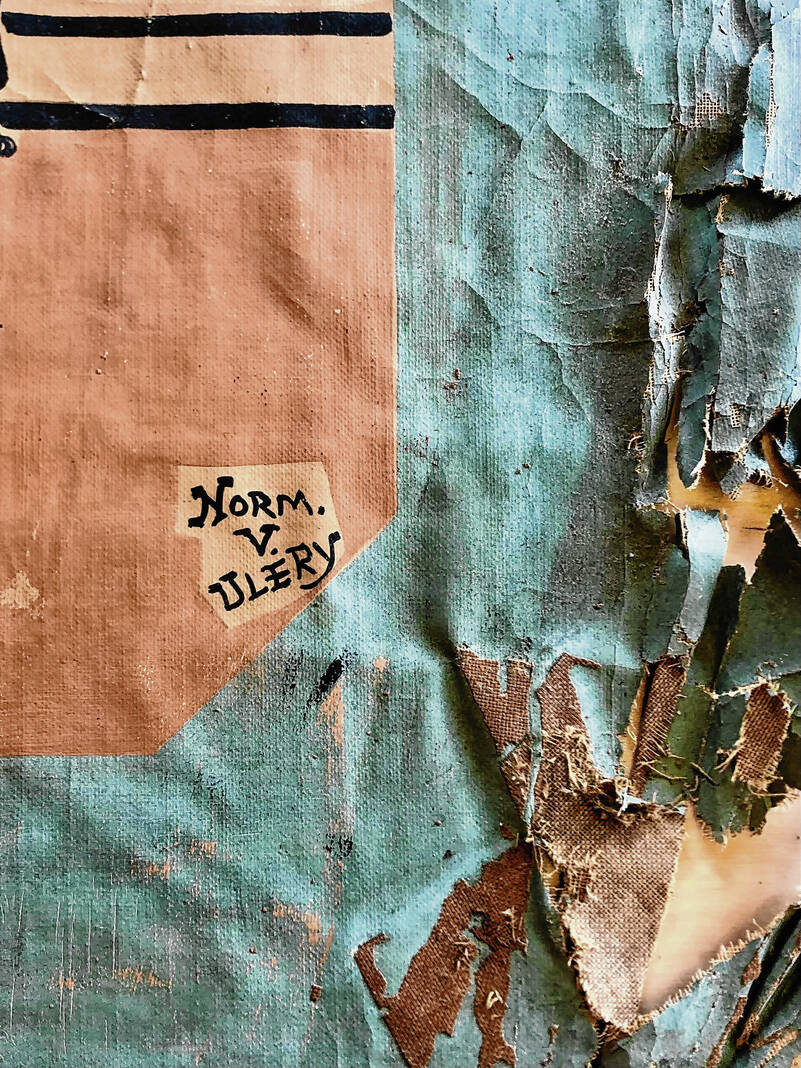

The banner was painted by local artist Norman V. Ulery ahead of the play and is one of 11 that have been conserved by Noggle.

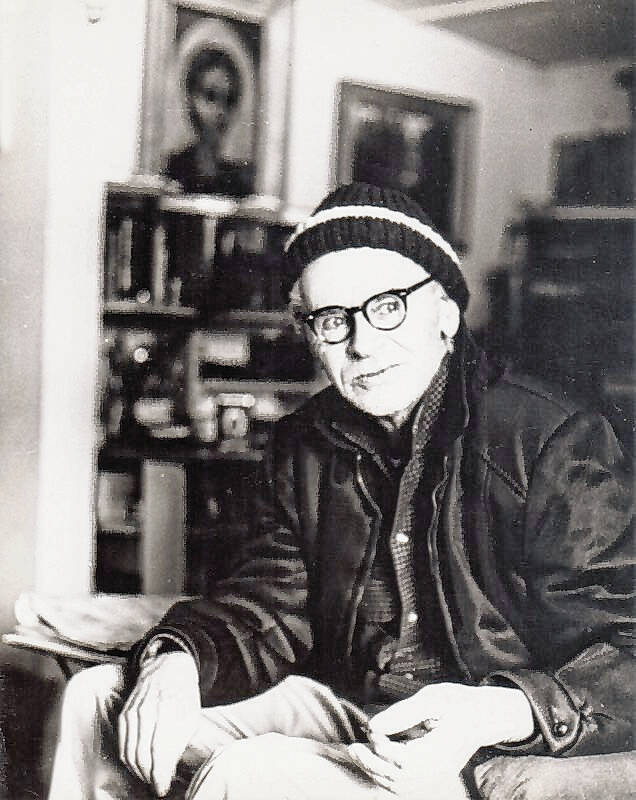

Ulery worked out of his home studio just outside of Nashville, the Red Shed Studio, where he painted contemporary, non-objective and cosmic art.

Ulery was born in Peru, Indiana Dec. 29, 1908 and died in Nashville on Sept. 8, 1976 — one year before the current Brown County Playhouse building was completed.

The majority of Ulery’s work was accomplished at his Red Shed Studio on Cemetery Ridge in Brown County after he, his wife Gertrude and cat Jinx moved from Los Angeles to Brown County in 1947.

The Playhouse has been an attraction in the center of downtown Nashville since 1949 when it was first established as a barn theater. It was a joint project between local businessman A. Jack Rogers and Indiana University.

With IU in need of an outlet for their theater department and Brown County needing evening entertainment, the two joined forces.

Andy Rogers gave the land to IU where the current building has stood since 1977 .

IU shuttered the Playhouse in 2010, and Brown County Playhouse Management Inc., a nonprofit management group, stepped in to take it over in 2011.

Ulery ended up working for Jack Rogers, who gave the artist a studio in the Village Green Building on East Main Street, as Ulery was painting in his home by kerosene lamp at the time.

Ulery’s daughter, Normajean MacLeod, still lives locally at 93 years old. She said the night the Playhouse was supposed to open with its first show, Jack Rogers looked to Ulery for help.

Without a sign distinguishing the original Playhouse, Jack Rogers turned to the artist and said, “Ulery — how in the hell is anybody going to know what this place is?”

Within hours, Ulery had designed the first Playhouse sign and show poster, MacLeod said.

According to the Red Shed Studio website, Ulery created the system of “old-fashioned” sign lettering still prevalent in Nashville today.

McLeod had been trying to find what happened to the posters when they were taken down, she said.

“I’m very happy they’re doing anything,” McLeod said of the banner project.

After the shows, Jack Rogers would hang the banners in the Nashville House as a way to promote the Playhouse. When the Nashville House closed, Brown County Playhouse board member Bob Kirlin said they were afraid they would disappear.

Earlier this spring, they were rediscovered by Nashville House owner and Jack Rogers’ granddaughter Andi Rogers-Bartels.

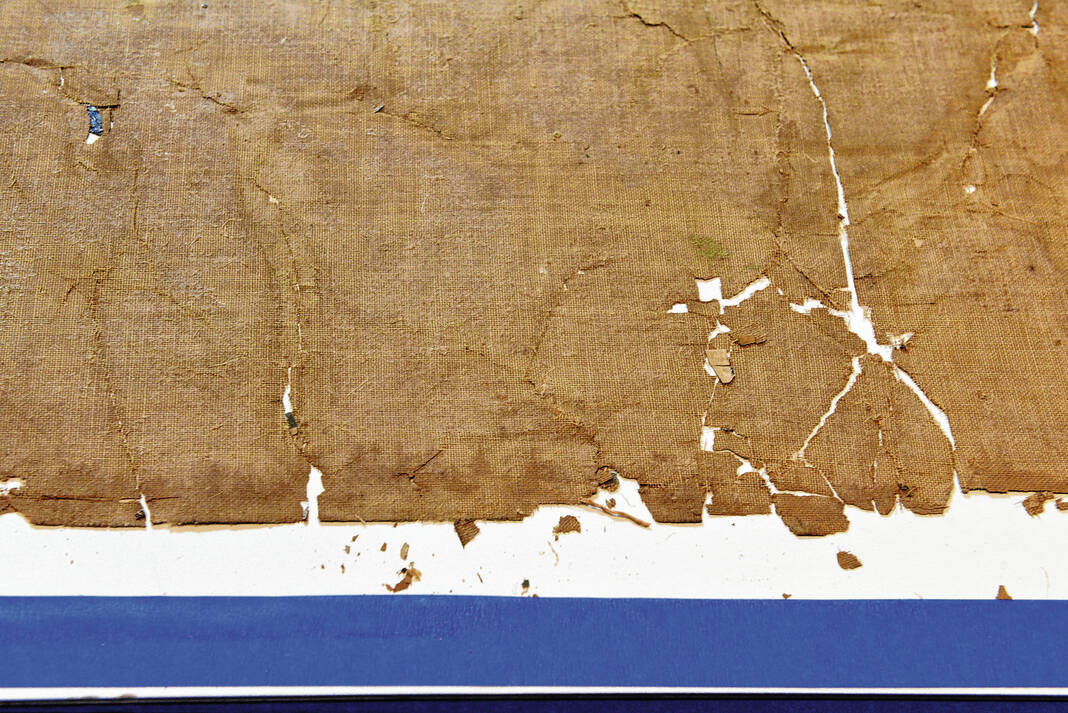

Years of hanging above the fireplace at the Nashville House covered the banners in a fine layer of smoke and soot. After they were brought down, the linen banners were folded and tucked away, gathering dust and dirt.

The timeworn pieces became quite dry from the conditions, also suffering from temperature changes, Noggle said, which dried out the paint and detracted from their suppleness.

After seeing their condition, the Playhouse board of directors then decided to commission a local artist to bring the works back to life.

They found Noggle, who decided to take on the challenge of conserving the work.

The project of restoring the banners is a somewhat massive undertaking, with Noggle investing about 10 hours into each piece.

Kirlin said the charge to conserve them was around $300 per banner, which was 100% donor-funded by local patrons.

Once completed, the banners will be on display at the Playhouse.

“We’re excited about it,” Kirlin said.

Challenge accepted

Bartels found nine banners folded up in the Nashville House. They had lived there for decades in hot, cold, heat and humidity, Noggle said.

As Noggle encouraged one banner to unfold, she found two more wrapped inside.

The oldest banner dated back to 1957, as detailed in the signature by Ulery.

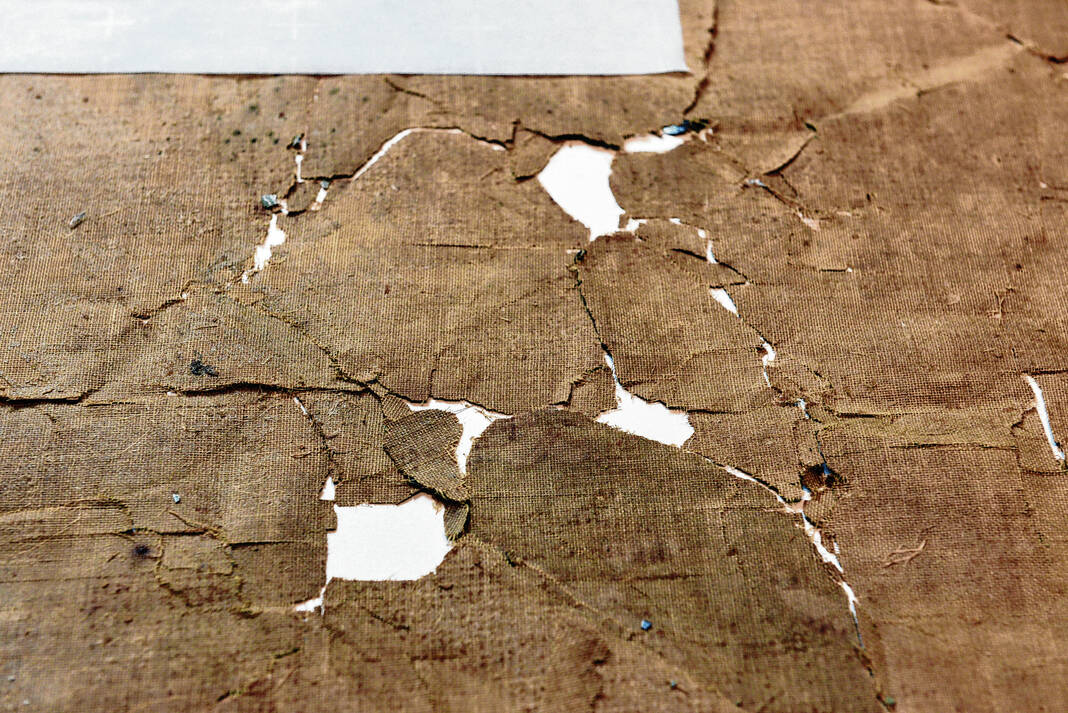

All the banners were painted by Ulery onto linen. The final piece, “East Lynne,” had been adhered to burlap then hung on a piece of wood from its corners.

This one, Noggle said, will be a donation of her time since it has exceeded the amount of time spent on the others by far.

“I don’t mind donating (my time) to the Playhouse,” she said with a fondness in her voice.

“East Lynne” is the closest to not being salvageable, but Noggle said she will still try, just for the challenge itself.

Brittle pieces lie separated from one another on a foam-core board, all varying sizes.

“It’s a good thing I grew up doing puzzles,” Noggle said.

As a child, Noggle remembers sitting on the back stoop of Rigley Art Supply Store, watching Playhouse performances that took place under the canvas tent — outside.

She lived in Brown County for six years as a child, which she said were formative years.

“I was very sad when we moved away,” she said. She and her family returned more than 10 years later, Brown County itself bringing them back.

The work has been done in stages, with the assistance of her daughter Sarabeth. First, the front and back are vacuumed with a bristle brush, a screen resting between the suction and the banner.

After that a special cleaner is used for any troublesome spots — sometimes it’s wiped down with a cotton cloth, other times a Q-tip.

They are finished with a sort of varnish and able to go from being delicately handled by four hands

“You have to have patience,” Noggle said. “But in the end it’s so gratifying.”

Noggle is a weaver, doing textile arts, embroidery work and felting. A spinning wheel in her family’s heritage was in her living room and she eventually learned how to spin, here in Brown County. That led her to Yarns Unlimited in Bloomington, where she worked there for around 20 years.

She teaches weaving classes around the Midwest and just returned from teaching a class in New Mexico.

Being a spinner is what led Noggle into textile conservation work, as it runs in the same scope, she said. Since the banner painting are on linen, it runs the same scope of textile work, using familiar and similar tools.

The refurbishing of the banners is also not restoration or preservation, but conservation.

If a work is restored, it will be made to look like the original.

“Conservation is stopping it in its tracks and not letting it get any worse,” Noggle said. “You’ll know that it’s been through a lot — but there’s history there.”

“They weren’t made to last for 60 to 70 years,” she continued.

Once she’s done, the work will remain intact for 30 years. When the process is completed, the viewer can see refreshed colors and new details, such as rosy cheeks, which were once hidden to the naked eye.

Being under the canvas of the first Brown County Playhouse in the pouring rain is a defined memory to Noggle, the show going on despite the weather.

“I just care for (the Playhouse), the history,” Noggle said. “It’s been my delight to do this.”