By KARA HAMMES, guest columnist

If I were to tell you about a habitat of “moist woodlands and areas of vegetation around the edge of forests, along forest trails, and in grassy fields,” would you think I was describing the average Brown County home, or the primary habitat of ticks?

Unfortunately, that’s a trick question, because the answer is both.

If you’ve been outside at all in Brown County, chances are you’ve encountered a tick, and likely more than one.

Ticks are vectors of a wide variety of diseases and are second only to mosquitoes in terms of public health importance worldwide. However, the most common vector-borne illness in North America is Lyme disease, which is spread by the black-legged tick.

[sc:text-divider text-divider-title=”Story continues below gallery” ]There are many species of ticks in the world (almost 900!), more than 90 of which occur in the continental United States.

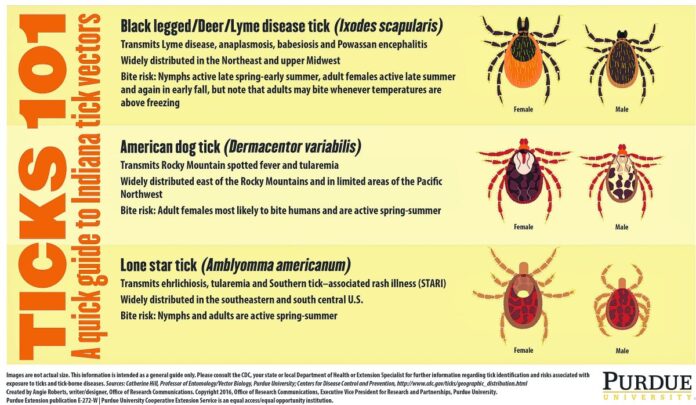

Ticks have a complex life cycle and may take several years to develop from an egg into their adult form and will feed on several different types of mammals along the way, including pets, livestock and humans. This multi-host feeding cycle is part of what causes disease to spread. Of the 15 tick species that have been documented in Indiana, at least three are of significance to public health:

- The American dog tick, also known as the “eastern wood tick” (Dermacentor variabilis) can transmit Rocky Mountain spotted fever and tularemia.

- The lone star tick (Amblyomma americanum) can transmit Lyme disease anaplasmosis, babesiosis and Powassan virus.

- The black-legged tick, also known as “deer tick” or “lyme disease tick” (Ixodes scapularis) — can transmit erlichiosis, tularemia, Lyme disease and Southern tick-associated rash illness and may also be linked to an allergic reaction to mammal products, a condition known as alpha-gal allergy.

- The Asian longhorned tick (Haemaphysalis longicornis) has been detected in North America, but hasn’t yet been documented in the Midwest. While Asian longhorned ticks in North America have not been shown to spread disease, in other countries this tick can transmit diseases like rickettsia, anaplasmosis and babesiosis.

My public health background has dealt mostly with infectious and vector-borne diseases, so while I have a personal fascination with this topic, I also have a hefty dose of respect for the potentially serious health impacts of tick-borne diseases.

Since we share habitat so closely with ticks here in Brown County, it’s important to take steps to protect yourself and your family from tick bites and exposure to tick-borne diseases.

The most common advice for preventing tick bites is to avoid their primary habitat during peak tick season, which is from early April into July in Indiana — although I know I’ve found ticks after hikes in February and late into the fall.

But, since it’s nearly impossible to avoid tick habitat in Brown County, there are other preventative steps you can take:

Clothes: Wear light-colored clothing. When hiking or walking in high grasses, this should include a long-sleeved shirt tucked into pants and long-legged pants tucked into socks. This will help to prevent ticks from reaching your body and also enable you to more easily spot adult ticks on your clothing.

Treat: Apply a repellent containing DEET, and consider treating clothing with permethrin, which repels and eventually kills ticks that contact clothing.

Check: Once you’re back inside, check your clothes, gear and body for ticks. Some ticks may be active even in the winter, so it is worth checking year-round. Ticks can wander on a host for up to several hours before they attach, so a thorough body check — with particular attention to the head, hairline, underarm and groin — can discover ticks before they begin to feed. If you can remove a tick within 24 hours of it attaching, you have a very low risk of acquiring disease.

Removal: Use tweezers to gently grasp the tick right behind the mouthparts, where the tick has attached to your skin. Pull gently and steadily until the tick releases its hold. Be careful not to break or squash the tick, as that could leave its mouthparts in your skin, or cause the tick to release body fluids back into the bite wound, both of which may increase your risk of infection. Using a match to burn the tick, smothering it with mayonnaise or other substances, or freezing it are not recommended methods for removal and could be harmful.

Once the tick is out, wash the wound with warm, soapy water and rubbing alcohol. The removed tick should be saved for identification. At a minimum, take a good picture with your cellphone before disposing of it in a sealable plastic bag in the garbage or flushing it down the toilet.

Disease: The good news is that disease transmission typically does not occur until an infected tick has attached and fed for at least 24 hours, and in some cases not until an infected tick has fed for 48 hours or more. Symptoms and skin reactions of tick-borne diseases can vary widely from person to person, and some people may be infected without showing any initial symptoms. It’s important to know if you’ve been in tick habitat or if you’ve gotten a tick bite so that you can notify your doctor immediately if you start to notice any symptoms. Seek medical advice if you have any concerns about a tick bite.

If you’d like to get involved with tick distribution mapping and sampling efforts in Indiana, consider joining the Tick INsiders program, a citizen science project to advance detection, diagnosis and treatment of tick-borne diseases in Indiana.

In 2019, Tick INsiders widened their sampling efforts to include all Indiana residents, and it’s not too late to join; you can learn more and watch a series of online training videos at their website, tickinsiders.org.

Kara Hammes is the Brown County Purdue Extension educator for Health & Human Sciences and Agriculture & Natural Resources. She can be reached at 812-988-5495 or [email protected].

[sc:pullout-title pullout-title=”On the Web” ][sc:pullout-text-begin]

Additional information about ticks can be found online at edustore.purdue.edu, including:

- “Ticks 101: A Quick Start Guide to Indiana Tick Vectors” (E-272-W);

- “Ticks — Biology and Their Control” (E-71-W); and

- “The Biology and Medical Importance of Ticks in Indiana” (E-243-W).